Transactions, Blocks, Mining, and the Blockchain

The bitcoin system, unlike traditional banking and payment systems, is based on decentralized trust. Instead of a central trusted authority, in bitcoin, trust is achieved as an emergent property from the interactions of different participants in the bitcoin sys‐ tem. In this chapter we will examine bitcoin from a high-level by tracking a single transaction through the bitcoin system and watch as it becomes “trusted” and accepted by the bitcoin mechanism of distributed consensus and is finally recorded on the block‐ chain, the distributed ledger of all transactions.

Each example below is based upon an actual transaction made on the bitcoin network, simulating the interactions between the users (Joe, Alice and Bob) by sending funds from one wallet to another. While tracking a transaction through the bitcoin network and blockchain, we will use a blockchain explorer site to visualize each step. A blockchain explorer is a web application that operates as a bitcoin search engine, in that it allows you to search for addresses, transactions and blocks and see the relationships and flows between them.

Popular blockchain explorers include:

• blockchain.info

• blockexplorer.com

• insight.bitpay.com

• blockr.io

Each of these has a search function that can take an address, transaction hash or block number and find the equivalent data on the bitcoin network and blockchain. With each example, we will provide a URL that takes you directly to the relevant entry, so you can study it in detail.

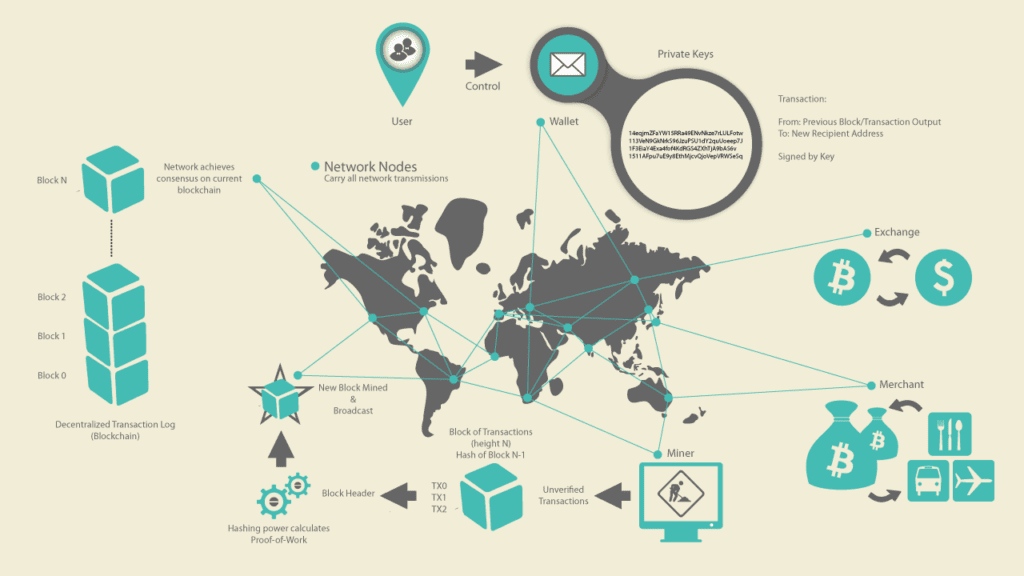

Bitcoin Overview

In the overview diagram below, we see that the bitcoin system consists of users with wallets containing keys, transactions which are propagated across the network and miners who produce (through competitive computation) the consensus blockchain, the authoritative ledger of all transactions. In this chapter, we will trace a single transaction as it travels across the network and examine the interactions between each part of the bitcoin system, at a high level. Subsequent chapters will delve into the technology behind wallets, mining and merchant systems.

Buying a cup of coffee

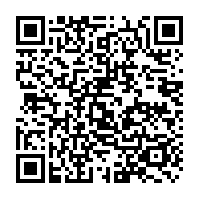

Alice, introduced in the previous chapter, is a new user who has just acquired her first bitcoin. In “Getting your first bitcoins” , Alice met with her friend Joe to exchange some cash for bitcoin. The transaction created by Joe, funded Alice’s wallet with 0.10 BTC. Now Alice will make her first retail transaction, buying a cup of coffee at Bob’s coffee shop in Palo Alto, California. Bob’s coffee shop recently started accepting bitcoin payments, by adding a bitcoin option to his point-of-sale system. The prices at Bob’s Cafe are listed in the local currency (US dollars) but at the register, customers have the option of paying in either dollars or bitcoin. Alice places her order for a cup of coffee and Bob enters the transaction at the register. The point-of-sale system will convert the total price from US dollars to bitcoins at the prevailing market rate and display the prices in both currencies, as well as showing a QR code containing a payment request for this transaction:

Displayed on Bob’s cash register.

Total:

$1.50 USD

0.015 BTC

The payment request QR code above encodes the following URL, defined in BIP0021.

bitcoin:1GdK9UzpHBzqzX2A9JFP3Di4weBwqgmoQA?\

amount=0.015&\

label=Bob%27s%20Cafe&\

message=Purchase%20at%20Bob%27s%20Cafe

Components of the URL

A bitcoin address: "1GdK9UzpHBzqzX2A9JFP3Di4weBwqgmoQA"

The payment amount: "0.015"

A label for the recipient address: "Bob's Cafe"

A description for the payment: "Purchase at Bob's Cafe"

Unlike a QR code that simply contains a destination bitcoin ad‐ dress, a “payment request” is a QR encoded URL that contains a destination address, a payment amount and a generic description such as “Bob’s Cafe”. This allows a bitcoin wallet application to pre-fill the information used to send the payment while showing a humanreadable description to the user. You can scan the QR code above with a bitcoin wallet application to see what Alice would see.

Bob says “That’s one-dollar-fifty, or fifteen milliBits”

Alice uses her smartphone to scan the barcode on display. Her smartphone shows a payment of 0.0150 BTC to Bob’s Cafe and she selects Send to authorize the payment. Within a few seconds (about the same time as a credit card authorization), Bob would see the transaction on the register, completing the transaction.

In the following sections we will examine this transaction in more detail, see how Alice’s wallet constructed it, how it was propagated across the network, how it was verified and finally how Bob, the owner of the cafe, can spend that amount in subsequent transac‐ tions.

The bitcoin network can transact in fractional values, e.g. from millibitcoins (1/1000th of a bitcoin) down to 1/100,000,000th of a bit‐ coin, which is known as a Satoshi. Throughout this book we’ll use the term “bitcoins” to refer to any quantity of bitcoin currency, from the smallest unit (1 Satoshi) to the total number (21,000,000) of all bit‐ coins that will ever be mined.

Bitcoin Transactions

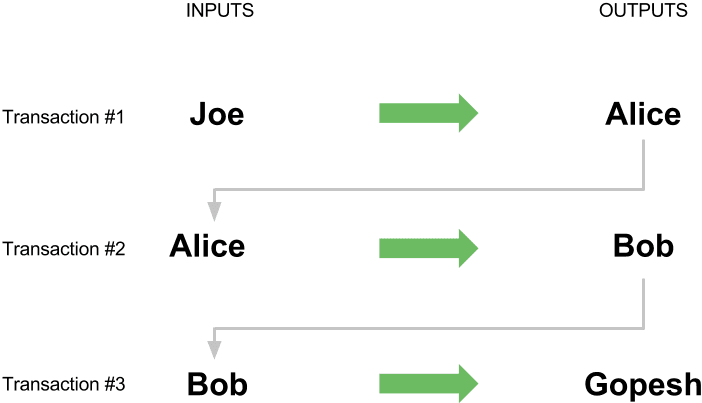

In simple terms, a transaction tells the network that the owner of a number of bitcoins has authorized the transfer of some of those bitcoins to another owner. The new owner can now spend these bitcoins by creating another transaction that authorizes transfer to another owner, and so on, in a chain of ownership.

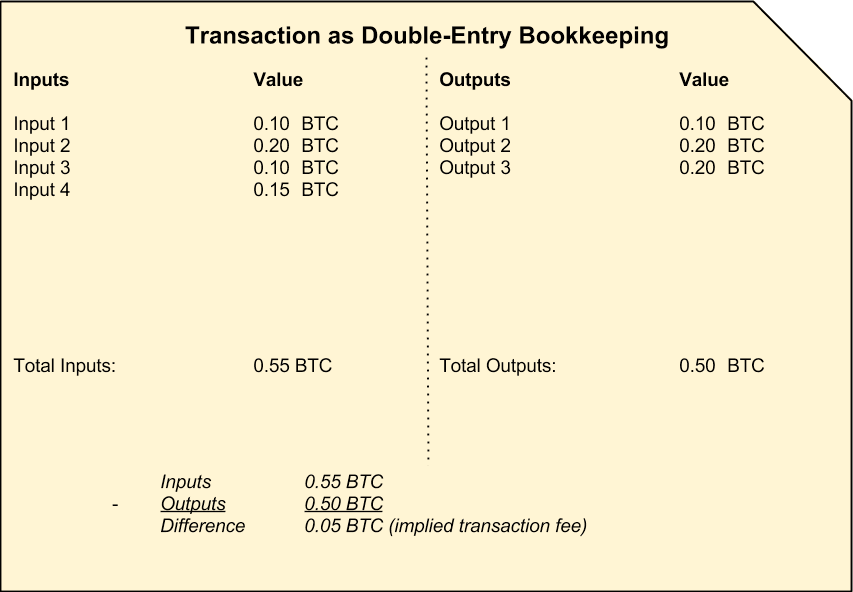

Transactions are like lines in a double-entry bookkeeping ledger. In simple terms, each transaction contains one or more “inputs”, which are debits against a bitcoin account. On the other side of the transaction, there are one or more “outputs”, which are credits added to a bitcoin account. The inputs and outputs (debits and credits) do not neces‐ sarily add up to the same amount. Instead, outputs add up to slightly less than inputs and the difference represents an implied “transaction fee”, a small payment collected by the miner who includes the transaction in the ledger.

The transaction also contains proof of ownership for each amount of bitcoin (inputs) whose value is transferred, in the form of a digital signature from the owner, which can be independently validated by anyone. In bitcoin terms, “spending” is signing a trans‐ action which transfers value from a previous transaction over to a new owner identified by a bitcoin address.

Transactions move value from transaction inputs to transaction out‐ puts. An input is where the coin value is coming from, usually a previous transaction’s output. A transaction output assigns a new owner to the value by associating it with a key. The destination key is called an encumbrance. It imposes a requirement for a signature for the funds to be redeemed in future transactions. Outputs from one transaction can be used as inputs in a new transaction, thus creating a chain of ownership as the value is moved from address to address.

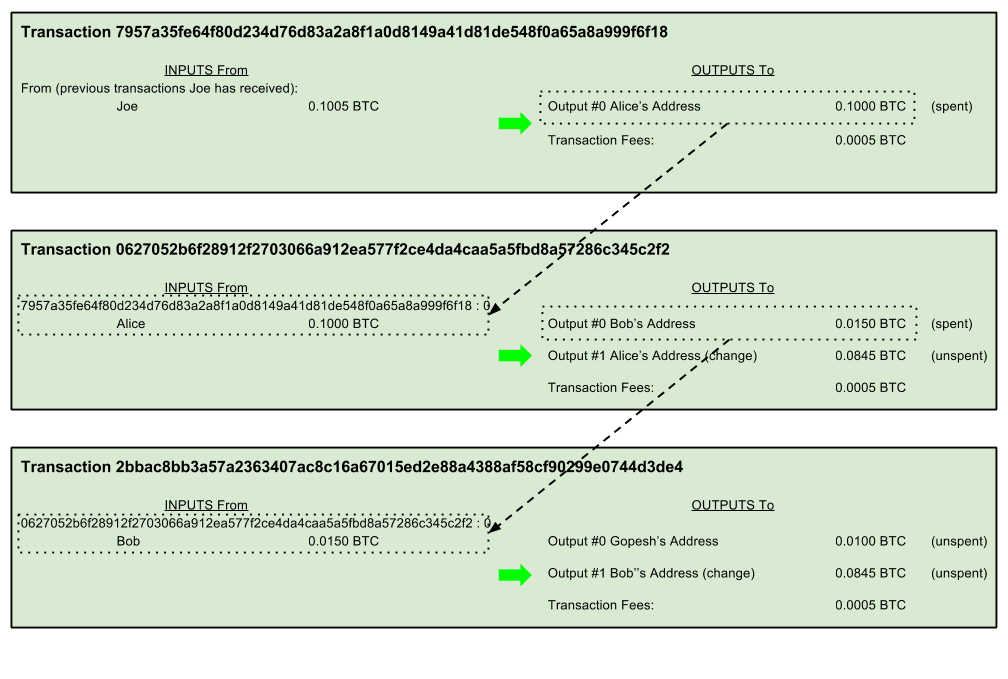

Alice’s payment to Bob’s Cafe utilizes a previous transaction as its input. In the previous chapter Alice received bitcoin from her friend Joe in return for cash. That transaction has a number of bitcoins locked (encumbered) against Alice’s key. Her new transaction to Bob’s Cafe references the previous transaction as an input and creates new outputs to pay for the cup of coffee and receive change. The transactions form a chain, where the inputs from the latest transaction correspond to outputs from previous transactions. Alice’s key provides the signature which unlocks those previous transaction outputs, thereby proving to the bitcoin network that she owns the funds. She attaches the pay‐ ment for coffee to Bob’s address, thereby “encumbering” that output with the require‐ ment that Bob produces a signature in order to spend that amount. This represents a transfer of value between Alice and Bob.

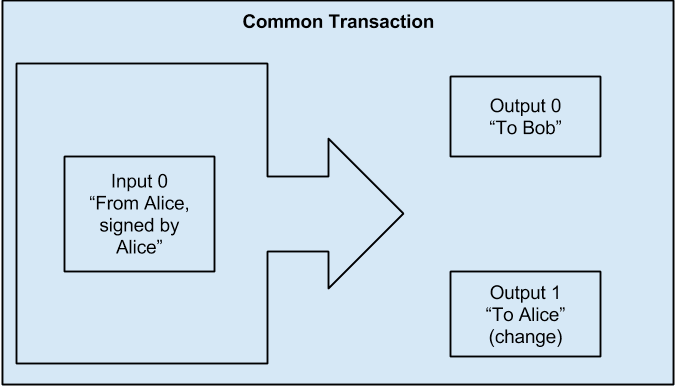

Common Transaction Forms

The most common form of transaction is a simple payment from one address to another, which often includes some “change” returned to the original owner. This type of trans‐ action has one input and two outputs and is shown below:

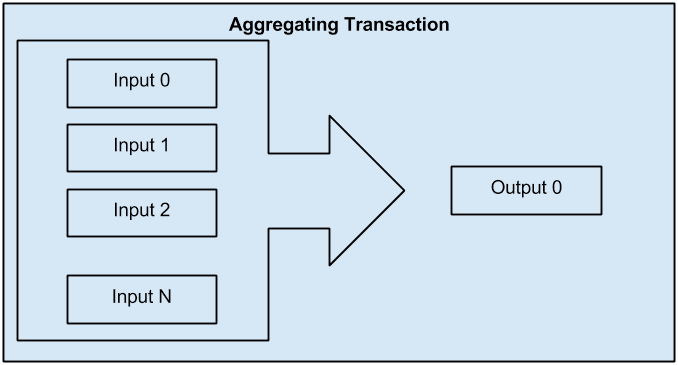

Another common form of transaction is a transaction that aggregates several inputs into a single output. This represents the real-world equivalent of exchanging a pile of coins and currency notes for a single larger note. Transactions like these are sometimes generated by wallet applications to clean up lots of smaller amounts that were received as change for payments.

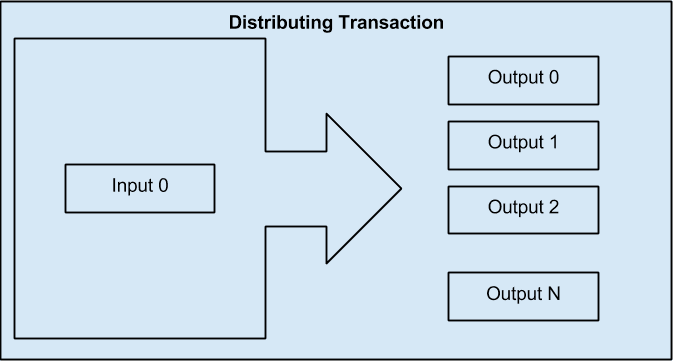

Finally, another transaction form that is seen often on the bitcoin ledger is a transaction that distributes one input to multiple outputs representing multiple recipients. This type of transaction is sometimes used by commercial entities to distribute funds, such as when processing payroll payments to multiple employees.

Constructing a Transaction

Alice’s wallet application contains all the logic for selecting appropriate inputs and out‐ puts to build a transaction to Alice’s specification. Alice only needs to specify a desti‐ nation and an amount and the rest happens in the wallet application without her seeing the details. Importantly, a wallet application can construct transactions even if it is completely offline. Like writing a cheque at home and later sending it to the bank in an envelope, the transaction does not need to be constructed and signed while connected to the bitcoin network. It only has to be sent to the network eventually for it to be executed.

Getting the right inputs

Alice’s wallet application will first have to find inputs that can pay for the amount she wants to send to Bob. Most wallet applications keep a small database of “unspent trans‐ action outputs” that are locked (encumbered) with the wallet’s own keys. Therefore, Alice’s wallet would contain a copy of the transaction output from Joe’s transaction which was created in exchange for cash (see “Getting your first bitcoins”). A bitcoin wallet application that runs as a full-index client actually contains a copy of every unspent output from every transaction in the blockchain. This allows a wallet to con‐ struct transaction inputs as well as to quickly verify incoming transactions as having correct inputs. However, since a full-index client takes up a lot of disk space, most user wallets run “lightweight” clients that track only the user’s own unspent outputs.

If the wallet application does not maintain a copy of unspent transaction outputs, it can query the bitcoin network to retrieve this information, using a variety of APIs available by different providers, or by asking a full-index node using the bitcoin JSON RPC API. Below we see an example of a RESTful API request, constructed as an HTTP GET command to a specific URL. This URL will return all the unspent transaction outputs for an address, giving any application the information it needs to construct transaction inputs for spending. We use the simple command-line HTTP client cURL to retrieve the response:

Look up all the unspent outputs for Alice’s bitcoin address.

{

"unspent_outputs":[

{

"tx_hash":"186f9f998a5...2836dd734d2804fe65fa35779",

"tx_index":104810202,

"tx_output_n": 0,

"script":"76a9147f9b1a7fb68d60c536c2fd8aeaa53a8f3cc025a888ac",

"value": 10000000,

"value_hex": "00989680",

"confirmations":0

}

]

}

The response above shows that the bitcoin network knows of one unspent output (one that has not been redeemed yet) under the ownership of Alice’s address 1Cdid9KFAaatwczBwBttQcwXYCpvK8h7FK. The response includes the reference to the transaction in which this unspent output is contained (the payment from Joe) and its value in Satoshis, at 10 million, equivalent to 0.10 bitcoin. With this information, Alice’s wallet application can construct a transaction to transfer that value to new owner ad‐ dresses.

Use the following link to look up the transaction from Joe to Alice:

https://blockchain.info/tx/0627052b6f28912f2703066a912ea577f2ce4da4caa5a5fbd8a57286c345c2f2

Adding the transaction to the ledger

The transaction created by Alice’s wallet application is 258 bytes long and contains everything necessary to confirm ownership of the funds and assign new owners. Now, the transaction must be transmitted to the bitcoin network where it will become part of the distributed ledger, the blockchain. In the next section we will see how a transaction becomes part of a new block and how the block is “mined”. Finally, we will see how the new block, once added to the blockchain is increasingly trusted by the network as more blocks are added.

Transmitting the transaction

Since the transaction contains all the information necessary to process, it does not mat‐ ter how or where it is transmitted to the bitcoin network. The bitcoin network is a peerto-peer network, with each bitcoin client participating by connecting to several other bitcoin clients. The purpose of the bitcoin network is to propagate transactions and blocks to all participants.

How it propagates

Alice’s wallet application can send the new transaction to any of the other bitcoin clients it is connected to over any Internet connection: wired, WiFi, or mobile. Her bitcoin wallet does not have to be connected to Bob’s bitcoin wallet directly and she does not have to use the Internet connection offered by the cafe, though both those options are possible too. Any bitcoin network node (other client) that receives a valid transaction it has not seen before, will immediately forward it to other nodes to which it is connected. Thus, the transaction rapidly propagates out across the peer-to-peer network, reaching a large percentage of the nodes within a few seconds.

Bob’s view

If Bob’s bitcoin wallet application is directly connected to Alice’s wallet application, Bob’s wallet application may be the first node to receive the transaction. However, even if Alice’s wallet sends the transaction through other nodes, it will reach Bob’s wallet within a few seconds. Bob’s wallet will immediately identify Alice’s transaction as an incoming payment because it contains outputs redeemable by Bob’s keys. Bob’s wallet application can also independently verify that the transaction is well-formed, uses previouslyunspent inputs and contains sufficient transaction fees to be included in the next block. At this point Bob can assume, with little risk, that the transaction will shortly be included in a block and confirmed.

A common misconception about bitcoin transactions is that they must be “confirmed” by waiting 10 minutes for a new block, or up to sixty minutes for a full six confirmations. While confirmations en‐ sure the transaction has been accepted by the whole network, such a delay is unnecessary for small value items like a cup of coffee. A merchant may accept a valid small-value transaction with no confir‐ mations, with no more risk than a credit card payment made without ID or a signature, like merchants routinely accept today.

Bitcoin Mining

The transaction is now propagated on the bitcoin network. It does not become part of the shared ledger (the blockchain) until it is verified and included in a block by a process called mining.

The bitcoin system of trust is based on computation. Transactions are bundled into blocks, which require an enormous amount of computation to prove, but only a small amount of computation to verify as proven. This process is called mining and serves two purposes in bitcoin:

• Mining creates new bitcoins in each block, almost like a central bank printing new money. The amount of bitcoin created per block is fixed and diminishes with time.

• Mining creates trust by ensuring that transactions are only confirmed if enough computational power was devoted to the block that contains them. More blocks mean more computation which means more trust.

A good way to describe mining is like a giant competitive game of sudoku that resets every time someone finds a solution and whose difficulty automatically adjusts so that it takes approximately 10 minutes to find a solution. Imagine a giant sudoku puzzle, several thousand rows and columns in size. If I show you a completed puzzle you can verify it quite quickly. However, if the puzzle has a few squares filled and the rest is empty, it takes a lot of work to solve! The difficulty of the sudoku can be adjusted by changing its size (more or fewer rows and columns), but it can still be verified quite easily even if it is very large. The “puzzle” used in bitcoin is based on a cryptographic hash and exhibits similar characteristics: it is asymmetrically hard to solve but easy to verify, and its difficulty can be adjusted.

In “Bitcoin Uses, Users and Their Stories” we introduced Jing, a computer engineering student in Shanghai. Jing is participating in the bitcoin network as a miner. Every 10 minutes or so, Jing joins thousands of other miners in a global race to find a solution to a block of transactions. Finding such a solution, the so-called “Proof-ofWork”, requires quadrillions of hashing operations per second across the entire bitcoin network. The algorithm for “Proof-of-Work” involves repeatedly hashing the header of the block and a random number with the SHA256 cryptographic algorithm until a solution matching a pre-determined pattern emerges. The first miner to find such a solution wins the round of competition and publishes that block into the blockchain.

Jing started mining in 2010 using a very fast desktop computer to find a suitable Proofof-Work for new blocks. As more miners started joining the bitcoin network, the dif‐ ficulty of the problem increased rapidly. Soon, Jing and other miners upgraded to more specialized hardware, such as Graphical Processing Units (GPUs), as used in gaming desktops or consoles. As this book is written, by 2014, the difficulty is so high that it is only profitable to mine with Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASIC), essentially hundreds of mining algorithms printed in hardware, running in parallel on a single silicon chip. Jing also joined a “mining pool”, which much like a lottery-pool allows several participants to share their efforts and the rewards. Jing now runs two USBconnected ASIC machines to mine for bitcoin 24 hours a day. He pays his electricity costs by selling the bitcoin he is able to generate from mining, creating some income from the profits. His computer runs a copy of bitcoind, the reference bitcoin client, as a back-end to his specialized mining software.

Mining transactions in blocks

A transaction transmitted across the network is not verified until it becomes part of the global distributed ledger, the blockchain. Every ten minutes on average, miners generate a new block that contains all the transactions since the last block. New transactions are constantly flowing into the network from user wallets and other applications. As these are seen by the bitcoin network nodes, they get added to a temporary “pool” of unverified transactions maintained by each node. As miners build a new block, they add unverified transactions from this pool to a new block and then attempt to solve a very hard problem (aka Proof-of-Work) to prove the validity of that new block.

Transactions are added to the new block, prioritized by the highest-fee transactions first and a few other criteria. Each miner starts the process of mining a new block of trans‐ actions as soon as they receive the previous block from the network, knowing they have lost that previous round of competition. They immediately create a new block, fill it with transactions and the fingerprint of the previous block and start calculating the Proof-of-Work for the new block. Each miner includes a special transaction in their block, one that pays their own bitcoin address a reward of newly created bitcoins (cur‐ rently 25 BTC per block). If they find a solution that makes that block valid, they “win” this reward because their successful block is added to the global blockchain and the reward transaction they included becomes spendable. Jing, who participates in a mining pool, has set up his software to create new blocks that assign the reward to a pool address. From there, a share of the reward is distributed to Jing and other miners in proportion to the amount of work they contributed in the last round.

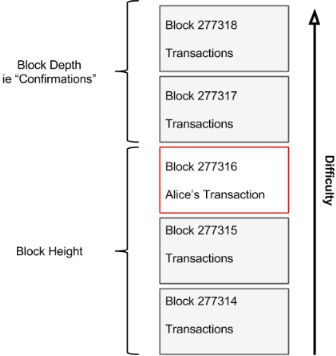

Alice’s transaction was picked up by the network and included in the pool of unverified transactions. Since it had sufficient fees, it was included in a new block generated by Jing’s mining pool. Approximately 5 minutes after the transaction was first transmitted by Alice’s wallet, Jing’s ASIC miner found a solution for the block and published it as block #277316, containing 419 other transactions. Jing’s ASIC miner published the new block on the bitcoin network, where other miners validated it and started the race to generate the next block.

You can see the block that includes Alice’s transaction here:

A few minutes later, a new block, #277317 is mined by another miner. As this new block is based on the previous block (#277316) that contained Alice’s transaction, it added even more computation on top of that block, thereby strengthening the trust in those transactions. One block mined on top of the one containing the transaction is called “one confirmation” for that transaction. As the blocks pile on top of each other, it be‐ comes exponentially harder to reverse the transaction, thereby making it more and more trusted by the network.

In the diagram below we can see block #277316, which contains Alice’s transaction. Below it are 277,316 blocks (including block #0), linked to each other in a chain of blocks (blockchain) all the way back to block #0, the genesis block. Over time, as the “height” in blocks increases, so does the computation difficulty for each block and the chain as a whole. The blocks mined after the one that contains Alice’s transaction act as further assurance, as they pile on more computation in a longer and longer chain. The blocks above count as “confirmations”. By convention, any block with more than 6 confirma‐ tions is considered irrevocable, as it would require an immense amount of computation to invalidate and re-calculate six blocks.

Spending the transaction

Now that Alice’s transaction has been embedded in the blockchain as part of a block, it is part of the distributed ledger of bitcoin and visible to all bitcoin applications. Each bitcoin client can independently verify the transaction as valid and spendable. Fullindex clients can track the source of the funds from the moment the bitcoins were first generated in a block, incrementally from transaction to transaction, until they reach Bob’s address. Lightweight clients can do a Simplified Payment Verification by confirming that the transaction is in the blockchain and has several blocks mined after it, thus providing assurance that the network accepts it as valid.

Bob can now spend the output from this and other transactions, by creating his own transactions that reference these outputs as their inputs and assign them new ownership. For example, Bob can pay a contractor or supplier by transferring value from Alice’s coffee cup payment to these new owners. Most likely, Bob’s bitcoin software will aggre‐ gate many small payments into a larger payment, perhaps concentrating all the day’s bitcoin revenue into a single transaction. This would move the various payments into a single address, utilized as the store’s general “checking” account. For a diagram of an aggregating transaction, see Figure 2-6.

As Bob spends the payments received from Alice and other customers, he extends the chain of transactions which in turn are added to the global blockchain ledger for all to see and trust. Let’s assume that Bob pays his web designer Gopesh in Bangalore for a new web site page. Now the chain of transactions will look like this:

This article has been published from the source link without modifications to the text. Only the headline has been changed.