With the aid of machine learning, researchers have discovered a method to quickly anticipate the ambient pH preferences of bacteria. The new strategy, developed by scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder, promises to support attempts at ecological restoration, agriculture, and even the creation of probiotics for health.

According to Noah Fierer, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at CU Boulder and a fellow of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), there are numerous bacteria that play significant ecological roles in every environment, but it is frequently unknown what conditions they prefer to live in. The purpose of this technique is to ascertain the fundamentals of their natural history.

The first stage, according to lead author Josep Ramoneda, a visiting scholar at CIRES, is to determine whether specific bacteria are more likely to survive in acidic, neutral, or basic environments. He added that with this method, one could predict how bacteria will respond to virtually any environmental change. Imagine, for instance, that sea level rise is causing a coastal wetland to receive more salty water. We can predict how bacteria will react to these environmental changes, according to Ramoneda.

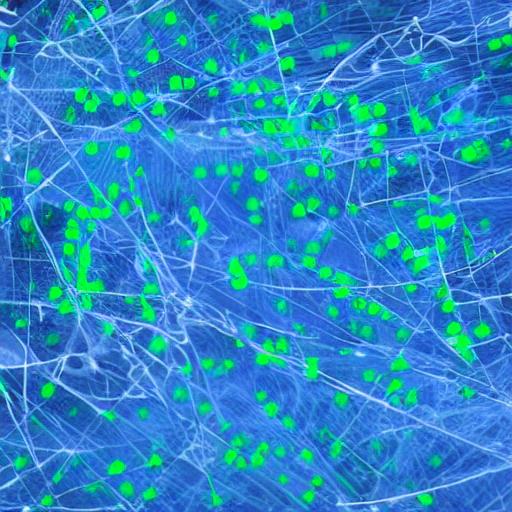

Microbes, especially bacteria, are essential to the health of ecosystems because they assist human digestion, help plants develop, and allow lakes to cycle nutrients. Ramoneda and Fierer noted that other than their genetic make-up, we frequently know nothing about them because they are frequently unable to isolate and develop in the lab. Recent advances in genetic “fishing” methods have resulted in databases of bacterial genomes that are expanding quickly.

The research team then employed machine learning to connect the environmental pH preferences of those groups with their genetic make-up. This was done by using what is known about a few bacterial groups that flourish at one particular pH or another. Almost 1,500 soil, lake, and stream samples were used in the work, which involved sorting through the genomes of over 250,000 different bacterial species.

According to Ramoneda, they discovered that they may deduce information about a person’s preferred pH level just from genomic data. One of the discovery’s most obvious consequences for scientists is that it may enable them to cultivate colonies of fussy bacteria that they have never been able to grow before by providing a first guess as to what pH to employ. The machine-learning approach could significantly speed up the years-long process of figuring out how to “culture” bacteria so they can be examined in the lab, according to Fierer.

According to Ramoneda, professionals in agriculture and forestry frequently mix in live bacteria to “inoculate” developing plants with advantageous bacterial populations. By assuring that inoculants would be tailored to the local pH, they may now gain quicker, better insight into the types of bacteria that might assist restore a native prairie as opposed to pine forests, or to better grow maize or soybeans.

The scientists will then attempt to gain understanding of bacteria’s preferred temperature, which is another intricate system that probably involves a huge number of genes. They might have a better understanding of, for instance, how warming will affect soil bacterial communities, thanks to this.

Fierer remarked that the painful option would be to attempt to develop them all in the lab.