According to a new analysis powered by artificial intelligence, biomedical research that aims to improve human health is especially dependent on publicly financed basic science.

According to research conducted by B. Ian Hutchins, a professor in the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Information School, a division of the School of Computer, Data & Informatics, clinical research in the same field cites published papers from the National Institutes of Health, which make up 10% of the published scientific literature, for about 30% of the substantive research—the significant contributions supporting even more new scientific findings. That is a considerable overrepresentation.

In published research papers, long sections listing all the prior works cited or supported the study are common. The Hutchins and Hoppe publication that you are currently reading cited no less than 64 additional papers and sources in its “References” section, predicting substantial biomedical citations without full text.

Citations signify the dissemination of information from one scientist (or team of scientists) to another. Although citations are carefully collected and tracked to evaluate the importance of specific studies and the researchers who conducted them, not all citations included in a given paper make equally significant contributions to the study they discuss.

According to Hutchins, we are taught that as scientists, we must provide some form of empirical support for whatever factual claims we make. There cannot be a small “citation needed here” mark like in Wikipedia entries. That citation is required. However, it doesn’t really support the idea that the information you’re referencing constitutes an essential earlier step towards your results if it doesn’t describe significant past work that you built upon.

Hutchins and his colleagues reasoned that citations added following publication, such as those that do so at the request of peer reviewers—the subject-matter experts who assess scientific papers submitted to journals—are less likely to have been actually significant to the authors’ study.

Hutchins asserts that if you are building on other people’s work, you most likely identified it earlier in the study procedure. Even while not all of the references in an early draught of the manuscript are crucial, the crucial ones are probably focused more in that earlier version.

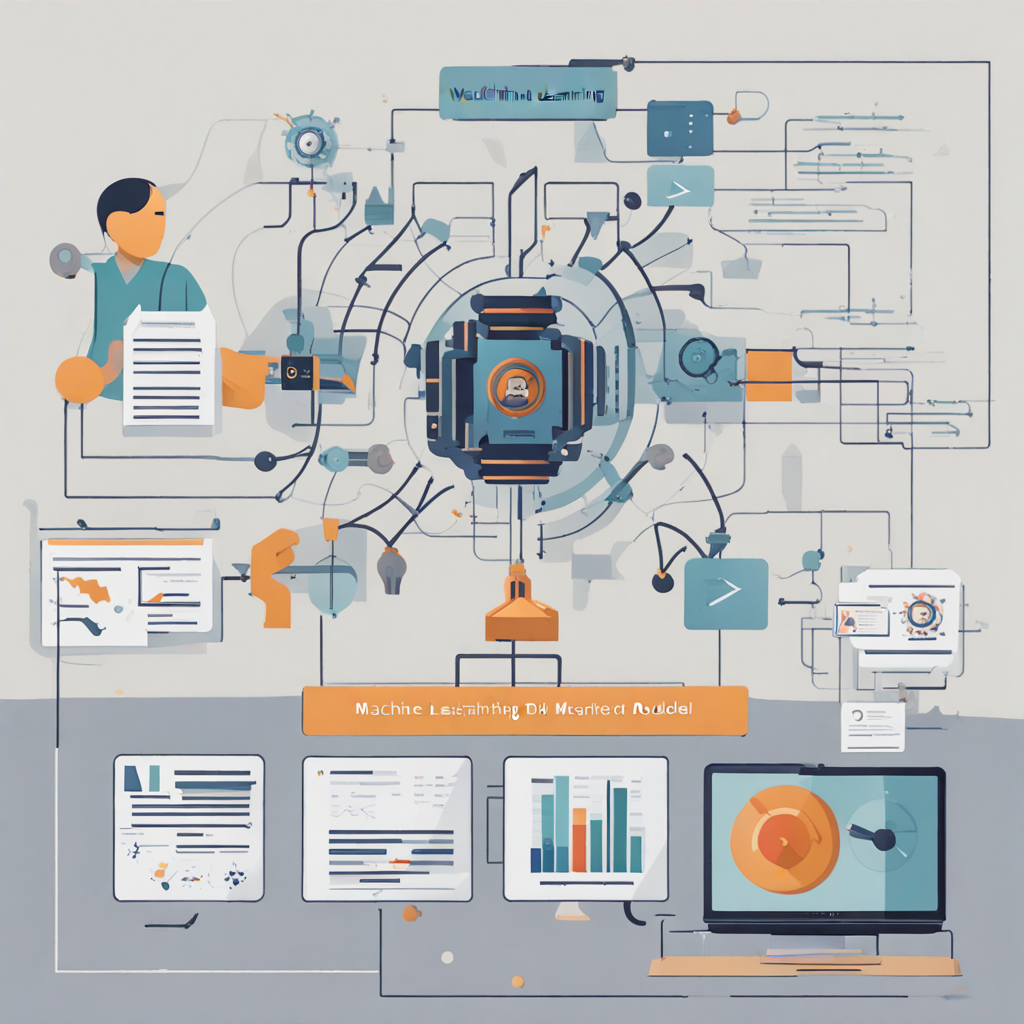

The researchers created a machine learning system to assess the value of citations by feeding it citation data from a pool of more than 38,000 scientific papers in order to distinguish between early and late citations. The citation information for each publication was available in two forms: the final published version that had completed peer review and the preprint version, which was made available to the public before peer review.

The algorithm discovered patterns to assist in identifying the citations that were more likely to be significant to each published scientific work. According to those findings, the proportion of NIH-funded fundamental biological science cited in the more important publications was three times higher than the proportion of all published research.

According to Hutchins, congressional leadership and members of the public frequently question the federal government’s support for basic research. This gives us concrete evidence—rather than simply anecdotes—that funding for basic research is crucial for fostering the kind of clinical research—patient treatments and cures—that Congress is generally more willing to support.