Artificial intelligence and machine learning exist on the back of a lot of hard work from humans.

Alongside the scientists, there are thousands of low-paid workers whose job it is to classify and label data – the lifeblood of such systems.

But increasingly there are questions about whether these so-called ghost workers are being exploited.

As we train the machines to become more human, are we actually making the humans work more like machines?

And what role do these workers play in shaping the AI systems that are increasingly controlling every aspect of our lives?

The most well-established of these crowdsourcing platforms is Amazon Mechanical Turk, owned by the online retail giant and run by its Amazon Web Services division.

But there are others, such as Samasource, CrowdFlower and Microworkers. They all allow businesses to remotely hire workers from anywhere in the world to do tasks that computers currently can’t do.

These tasks could be anything from labelling images to help computer vision algorithms improve, providing help for natural language processing, or even acting as content moderators for YouTube or Twitter.

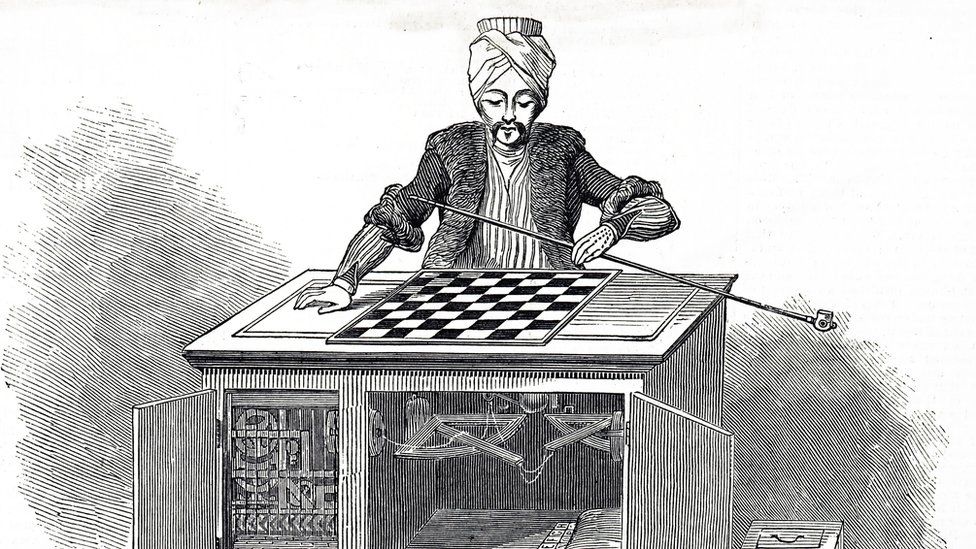

MTurk, as it is known, is named after an 18th Century chess-playing automaton which toured Europe – but was later revealed to have a human behind it.

The platform is billed on its website as a crowdsourcing marketplace and “a great way to minimise the costs and time for each stage of machine-learning development”.

It is a marketplace where requesters ask workers to perform a specific task.

“Most workers see MTurk as part-time work or a paid hobby, and they enjoy the flexibility to choose the tasks they want to work on and work as much or as little as they like,” said a AWS spokesman.

But for Sherry Stanley, who has been working for the platform for six years, it is more like a full-time job, one that helped her financially bring up her three children, but one that has also made her feel like a very small cog in a very big machine.

“Turking is one of the few job opportunities I have in West Virginia, and like many other Turk workers, we pride ourselves on our work,” she told the BBC.

“However, we are at the whim of Amazon. As one of the largest companies in the world, Amazon relies on workers like me staying silent about the conditions of our work.”

She said she lived “in constant fear of retaliation for speaking out about the ways we’re being treated”.

It is hard to describe a typical day for Sherry because, as she puts it, “the hours vary day by day and the pay also varies”.

But the tasks she is asked to complete are various, including image tagging and helping smart assistant Alexa understand regional dialects.

And there are also a series of issues she wants answers to, such as:

- why some work is rejected and why workers, who may have spent a long time on it, are not told the reason that it was not up to standard

- why some accounts are suddenly suspended without notice or official avenues for challenging the suspension

- why requesters are setting the price of some projects at extremely low rates

“Turk workers deserve greater transparency around the who, what, why and where of our work: why our work is rejected, what our work is building, why accounts are suspended, where our data goes when it’s not paid for, and who we are working for.

Turkopticon is the closest thing MTurk workers have to a union, and the advocacy group is working to make them feel less invisible.

“Turkopticon is the one tool that Turkers have evolved into an organisation to engage with each other about the conditions of our work and to make it better,” said Ms Stanley

She is fundraising to help the organisation create a worker-operated server where contractors can to talk to each other about working conditions.

In response, Amazon told the BBC that it had introduced a feature in 2019 that allowed workers to see “requester activity level, their approval rate and average payment review time”.

In a statement, it said: “While the overall rate at which workers’ tasks are rejected by requesters is very low (less than 1%), workers also have access to a number of metrics that can help them determine if they want to work on a task, including the requester’s historical record of accepting tasks.

“MTurk continues to help a wide range of workers earn money and contribute to the growth of their communities.”

Saiph Savage is the director of the Human Computer Interaction Lab at West Virginia University, and her research found that for a lot of workers, the rate of pay can be as low as $2 (£1.45) per hour – and often it is unclear how many hours someone will be required to work on a particular task.

“They are told the job is worth $5 but it might take two hours,” she told the BBC.

“Employers have much more power than the workers and can suddenly decide to reject work, and workers have no mechanism to do anything about it.”

And she says often little is known about who the workers on the platforms are, and what their biases might be.

She cited a recent study relating to YouTube that found that the algorithm had banned some LGBTQ content.

“Dig beneath the surface and it was not the algorithm that was biased but the workers behind the scenes, who were working in a country where there was censoring of LGBTQ content.”

This idea of bias is born out by Alexandrine Royer, from the Montreal AI Ethics Institute, who wrote about what she described as the urgent need for more regulation for these workers.

“The decisions made by data workers in Africa and elsewhere, who are responsible for data labelling and content moderation decisions on global platforms, feed back into and shape the algorithms internet users around the world interact with every day,” she said.

“Working in the shadows of the digital economy, these so-called ghost workers have immense responsibility as the arbiters of online content.”

Google searches to tweets to product review rely on this “unseen labour”, she added.

“It is high time we regulate and properly compensate these workers.”